After antiquing the entire morning at the brocante we went for lunch, we celebrated with our friend Joanne who had just received a copy of her new book (more about that tomorrow) plus we talked about what each of us had found during our morning hunt.

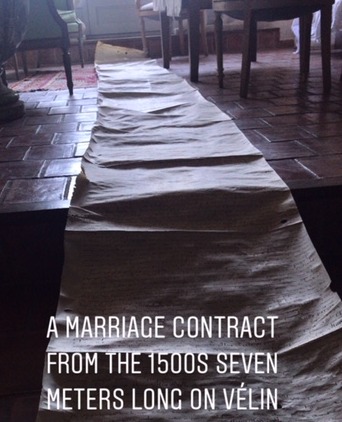

Later with renewed energy, we went back to take a second look, I enjoy going back and walking the opposite way around at the brocante, taking it slow, looking under tables, in the back of the vans, looking at things I normally don't look at the first several times around, and then just like that this thick vélin / parchment roll stared at me. I couldn't believe that I had not seen it and that it was still there late in the afternoon. Somethings are just meant to be yours. Somethings take a long time to come into your hands, but when they do it has an amazing effect like the stars are lining up, that flowers are blooming a crown on your head and or that you feel like shouting, "Amazing Grace!" I gave a squeal.

A thirteen panel, hand-sewn into a seven meters long marriage contract between two Nobel families sat on a table as if it were something as common as a baguette and cheese sandwich. At the brocante I never know what I am going to find but one thing is certain it never fails my imagination.

I bought it, and hope to sell it one day but would be hard to accept if someone was going to cut it up, so maybe I will donate it to a museum, or maybe open my own museum. If you are in Provence come on over and see it.

Text via The History of Vellum by This fascinating blog post about the history of vellum and parchment is written by Richard Norman, an experienced British bookbinder now living in France, where he runs Eden Workshops with his wife and fellow bookbinder, Margaret, specializing in Family Bibles and liturgical books. The article originally appeared on www.edenworkshops.com,

"According to the Roman Varro and Pliny's Natural History, vellum and parchment were invented under the patronage of Eumenes of Pergamum, as a substitute for papyrus, which was temporarily not being exported from Alexandria, its only source.

Herodotus mentions writing on skins as common in his time, the 5th century BC; and in his Histories (v.58) he states that the Ionians of Asia Minor had been accustomed to give the name of skins (diphtherai) to books; this word was adapted by Hellenized Jews to describe scrolls. Parchment (pergamenum in Latin), however, derives its name from Pergamon, the city where it was perfected (via the French parchemin). In the 2nd century B.C. a great library was set up in Pergamon that rivaled the famous Library of Alexandria. As prices rose for papyrus and the reed used for making it was over-harvested towards local extinction in the two nomes of the Nile delta that produced it, Pergamon adapted by the increasing use of vellum and parchment.

Writing on prepared animal skins had a long history, however. Some Egyptian Fourth Dynasty texts were written on vellum and parchment. Though the Assyrians and the Babylonians impressed their cuneiform on clay tablets, they also wrote on parchment and vellum from the 6th century BC onward. Rabbinic culture equated the idea of a book with a parchment scroll. Early Islamic texts are also found on parchment.

One sort of parchment is vellum, a word that is used loosely to mean parchment, and especially to mean a fine skin, but more strictly refers to skins made from calfskin (although goatskin can be as fine in quality). The words vellum and veal come from Latin vitulus, meaning calf, or its diminutive vitellus.

In the Middle Ages, calfskin and split sheepskin were the most common materials for making parchment in England and France, while goatskin was more common in Italy. Other skins such as those from large animals such as horse and smaller animals such as squirrel and rabbit were also used. Whether uterine vellum (vellum made from aborted calf fetuses) was ever really used during the medieval period is still a matter of great controversy.

There was a short period during the introduction of printing where parchment and paper were used interchangeably: although most copies of the Gutenberg Bible are on paper, some were printed on animal skins.

In 1490, Johannes Trithemius preferred the older methods, because "handwriting placed on the skin will be able to endure a thousand years. But how long will printing last, which is dependent on paper?

For if …it lasts for two hundred years that is a long time."

In the later Middle Ages, the use of animal skins was largely replaced by paper. New techniques in paper milling allowed it to be much cheaper and more abundant than parchment. With the advent of printing in the later fifteenth century, the demands of printers far exceeded the supply of vellum and parchment.

The heyday of parchment use was during the medieval period, but there has been a growing revival of its use among contemporary artists since the late 20th century. Although it never stopped being used (primarily for governmental documents and diplomas) it had ceased to be a primary choice for artist's supports by the end of 15th century Renaissance. This was partly due to its expense and partly due to its unusual working properties." Via The History of Vellum

To continue reading please follow the links above.

Leave a Reply